MAGAZINE

Black Woman Poets of the Harlem Renaissance that You Should All Know

by Nox Blair

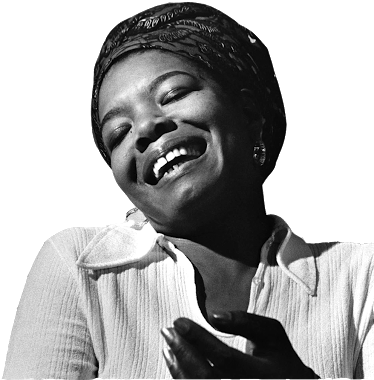

Black History Month is coming up and what better way to start that off by acknowledging the women that contributed to the Black Arts movement during the Harlem Renaissance. The Black Arts movement was an integral part of history that gained popularity during the Harlem Renaissance era and demonstrated political activism through all forms of artistic expression. It became popular among members of the African diaspora centered in the United States. Although women poets aren’t as well known and talked about as their male counterparts, they have still left a substantial impact on the literary world. Perhaps a good place to start off with is a poet who the public has heard of and who might have read some of her poems in high school–Maya Angelou.

One couldn’t forget one of the most talked about and memorable female poets of the 20th century that bled into the 21st century–Maya Angelou. Her work has been discussed in many high school and college classrooms and she is a well-known close friend of successful Black talk-show host, Oprah Winfrey. She worked for Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, and was even an educator herself. Her writings include (and are not limited to) Black rights, personal experiences, and Black feminism.

In the early 1960s, Maya Angelou had the luxury of going back to Ghana and experiencing what many Black Americans were afraid of. She thought to herself–was this what she was missing this whole time in her adult and childhood? She compared the skin of Ghanaians to some of her favorite foods and snacks and began questioning if Ghana could be a home for her still. She then goes on to compare Ghana to heaven. Of course, this didn’t last long as she began to be reminded that her ancestors were seen as “weak” by natives and the transatlantic slave trade began to peg her (Smithers).

Most of her popularized work isn’t focused around the Black American experience, but more so her own experience, experiences of other women, and female empowerment in general. I found that quite interesting considering she was one of few women that was able to travel outside of the America and to Ghana. I find this poem coming up not only tackles the “Angry Black Woman” schema and the sexualization of Black women but this poem also uplifts women who are consistently being put down for showing a bit of edge. It’s one of my favorite poems of Maya Angelou and one of the first I’ve read in high school.

You may write me down in history

With your bitter, twisted lies,

You may trod me in the very dirt

But still, like dust, I’ll rise.

Does my sassiness upset you?

Why are you beset with gloom?

’Cause I walk like I’ve got oil wells

Pumping in my living room.

Just like moons and like suns,

With the certainty of tides,

Just like hopes springing high,

Still I’ll rise.

Did you want to see me broken?

Bowed head and lowered eyes?

Shoulders falling down like teardrops,

Weakened by my soulful cries?

Does my haughtiness offend you?

Don’t you take it awful hard

’Cause I laugh like I’ve got gold mines

Diggin’ in my own backyard.

You may shoot me with your words,

You may cut me with your eyes,

You may kill me with your hatefulness,

But still, like air, I’ll rise.

Does my sexiness upset you?

Does it come as a surprise

That I dance like I’ve got diamonds

At the meeting of my thighs?

Out of the huts of history’s shame

I rise

Up from a past that’s rooted in pain

I rise

I’m a black ocean, leaping and wide,

Welling and swelling I bear in the tide.

Leaving behind nights of terror and fear

I rise

Into a daybreak that’s wondrously clear

I rise

Bringing the gifts that my ancestors gave,

I am the dream and the hope of the slave.

I rise

I rise

I rise.

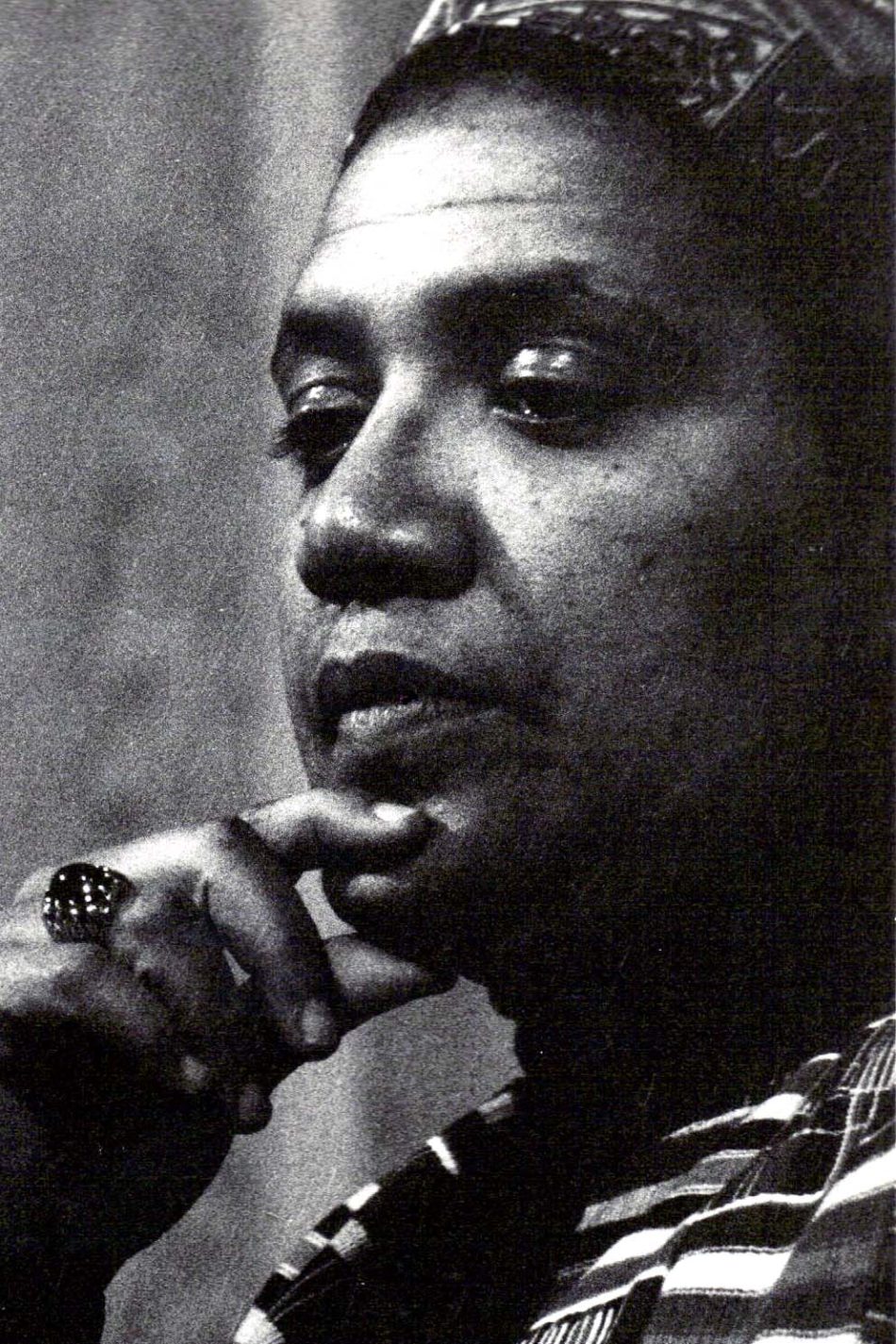

Audre Lorde, an influential Black lesbian social feminist poet, is among the most intriguing poets I know of. She was out and open about her sexuality and played a big part in advocating second-wave feminism and speaking out on Black rights simultaneously. In response to this, the term Womanism, whose originator seems to be Alice Walker, developed as many Black women came to recognize that feminism favored white women while ignoring women of color, specifically black women.

Speak earth and bless me with what is richest

make sky flow honey out of my hips

rigis mountains

spread over a valley

carved out by the mouth of rain.

And I knew when I entered her I was

high wind in her forests hollow

fingers whispering sound

honey flowed

from the split cup

impaled on a lance of tongues

on the tips of her breasts on her navel

and my breath

howling into her entrances

through lungs of pain.

Greedy as herring-gulls

or a child

I swing out over the earth

over and over

again.

This poem, Love Poem, was published in 1975 about an intimate love interaction between Lorde and another woman. In the 70s, sexuality was still taboo and seen as “white evil” in Black communities, but Lorde was very open on her sexuality in her writings and everywhere she could verbalize her intersectionality (Bowles). In a time when women were told to sit back and be quiet–let the men do the work–Audre did the complete opposite which many women found admirable.

Gayl Jones wasn’t just a poet, she was also a novelist and playwright. She was an extremely talented and outspoken woman who, like rappers, finds the beauty of their culture in (some may say) problematic ways. Before doing so, of course, “Jones prodigiously established a powerful and sometimes problematic dialectic between aesthetic experimentation–a highly unique combination of clinical psychology, eroticism, and applied African American musical elements (ritual, myth, repetition)–and the cultural investigation of what it means to be a modern African American woman” (Clabough).

Since Jones’ work went against always portraying Blackness in a positive light during the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and 1970s, her work was often isolated from other Black works. Despite how uncomfortable and pragmatic Jones’ work was to many, it still fit Marable’s general definition of Afrocentrism: “A positive Black consciousness that is anchored in the knowledge of African culture and history” (Clabough). Jones never portrayed Black culture in a “Uncle Tom” manner, but only combated troubling cultural themes and dilemmas that are concerned with the importance of constructive tasks of earnestly defining and exploring African American consciousness, and the significant events that shaped it.

She was very interested in the lives of other people of the African Diaspora and wasn’t focused on just African Americans. She has two poems which the narratives are portrayed by Brazilian milieus. Upon being interviewed for the novels The Healing (1998) and Mosquito (1999), which are books that contain international characters of the African Diaspora, Jones expressed a desire to capture the universal Black experience and went on to explain where her interest of Brazilian history stemmed from. To summarize, she felt that a lot of Black literary works in America are filled with racism and racial conflict rather than Black culture itself. In other places around the world where there are Black people living and prospering in their communities that aren’t tarnished by Black and White racism, she’s able to write about it fictionally without it feeling like an autobiography and escaping the restrictions of a “certain American World” (Clabough).

Mari Evans was another important and talented Black female poet of the 20th century. She was one of the most interesting 20th century poets I found–mainly because I couldn’t find much about her upon searching. Mainly because, like Gayl Jones, she tackled topics that Black people (at the time) did not want to engage with or read about at the time. I could tell by her work that she was more of a Black Panther/Malcolm X follower than a Martin Luther King Junior follower. Despite many people believing that Malcom was only about Black Unity and Martin was for equality–they both believed in the same thing and just went about that in different ways.

i’m

gonna put black angels

in all the books and a black

Christchild in Mary’s arms i’m

gonna make black bunnies black

fairies black santas black

nursery rhymes and

black

ice cream (“Vive Noir” 72-3).

This poem in particular was compelling as it really shows that Mari was really for the reformation of Black people specifically in America where Christianity was forced upon her ancestors and popularized.

Evans felt that Black art and the Black Art Movement was key to awakening black consciousness which would help people ‘become’ Black. In contrast to many other Black writers during this time, her work was quite unique. She states her work speaks to Black people, not for Black people. Although all of this might sound confusing because it seems that a lot of Black poets’ focus was also Evans focus, but the thing that stuck out more was the fact that she felt that she was helping Black people become more Black–she felt as if Black people, although “free,” were still chained to this white American mindset that was stopping them from achieving the highest rank of Black consciousness, from which she believed she had already reached. This of course adds onto the abuse and violence against Black people in America that she writes about in her poetry (Matthews).

Gwendolyn Brooks rose to fame as one of the most influential Black poets of the 20th century, using her writing skills as a way to speak out against stereotypes and racism, thus showing that she was passionate about social justice and societal norms. Her writing is mostly about poor people of color, black rights, and women’s liberation in the 1950′s and 60′s.

“In her autobiography, Report from Part Two, she quotes the African-American poet Sonia Sanchez, who told her, “You demystified the Library!” Brooks commented, “True! To my great delight they came—to talk about poetry. Male, female; from nine to ninety. Heterosexual, homosexual, etc. Jew. Gentile. Muslim. Aristocrat, beggar. Domestic, foreign. Senator, scientist. The sinful and the saintly. A bag lady.” Brooks spent her entire career in a humanistic effort to raise up those who were oppressed and to find inventive ways for poetry to participate in that project” (Axelrod).

Gwendolyn Brooks was born in Kansas but raised in a Chicago neighborhood called Bronzeville. In her younger years, she found herself reading and being inspired by poets such as Ezra Pound and T.S Elliot. She even had the pleasure of meeting Langston Hughes, who told her she was a great writer and that she should keep on writing. She went on to win the Pulitzer Prize in 1949, being the first African American to win one, with her second volume Annie Allen.

We real cool. We

Left school. We

Lurk late. We

Strike straight. We

Sing sin. We

Thin gin. We

Jazz June. We

Die soon.

This poem was written in 1959 and published in 1960 in her book The Bean Eaters. This is one of her most widespread and talked about poems in literature classes for many reasons–how short and to the point it is, and yet how hard it hits for people once you easily dissect what Brooks is talking about in this poem.

For Black History Month, it’s important to remember and acknowledge the women who contributed and powered through the Harlem Renaissance era by using their platform–even if women weren’t as recognized. I hope you’ve learned something new or read something interesting from these five amazing female poets.

Works Cited

Brooks, Gwendolyn. “The Bean Eaters.” New York, Harper (1960).

Clabough, Casey. “Afrocentric Recolonizations: Gayl Jones’s 1990s Fiction.” Contemporary Literature 46, no. 2 (2005): 243-74. www.jstor.org/stable/4489116.

GWENDOLYN BROOKS: (1917–2000).” In The New Anthology of American Poetry: Postmodernisms 1950-Present, edited by Axelrod Steven Gould, Roman Camille, and Travisano Thomas, 106-17. NEW BRUNSWICK, NEW JERSEY; LONDON: Rutgers University Press, 2012. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1bj4sjv.16.

HIGASHIDA, CHERYL. “Audre Lorde Revisited: Nationalism and Second-Wave Black Feminism.” In Black Internationalist Feminism: Women Writers of the Black Left, 1945-1995, 134-57. Urbana; Chicago; Springfield: University of Illinois Press, 2011. www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/j.ctt2tt9dg.9.

Matthews, Kristin L. “Neither Inside Nor Outside: Mari Evans, the Black Aesthetic, and the Canon.” CEA Critic 73, no. 2 (2011): 34-54. www.jstor.org/stable/44378442.

“Remembering Audre Lorde (1993).” In New Black Feminist Criticism, 1985-2000, edited by Bowles Gloria, Fabi M. Giulia, and Keizer Arlene R., by Christian Barbara, 164-68. University of Illinois Press, 2007. www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/j.ctt1xcfc6.21.

SMITHERS, GREGORY D. “Challenging a Pan-African Identity: The Autobiographical Writings of Maya Angelou, Barack Obama, and Caryl Phillips.” Journal of American Studies 45, no. 3 (2011): 483-502. doi:10.2307/23016785.

“Still I Rise by Maya Angelou – Poems | Academy of American Poets.” Poets.org. Academy of American Poets. https://poets.org/poem/still-i-rise.