MAGAZINE

The importance of idleness, digital intimacy and AI capitalism with Miche & Stan

Michelle and Stan are an interdisciplinary art and design partnership established in late 2020. Their practice emerged into and has experienced the entirety of its evolution so far, during an era of dizzying, precarity and change. Carrying a strong belief that the role of design is to adapt and learn in times of transition, they’ve found opportunities for fruitful creativity by exploring how to invite surprise and the unexpected into their process.

Could you tell me a little bit about yourselves and your work?

We are a duo of transdisciplinary designers who explore topics of automation, post-work imaginaries and queer temporalities through performative and tactile experiments. We’re inspired by useless robots, the morning routines of billionaires and absurd life-hack videos, and look to turn algorithms inside out, revealing the soft, fleshy bits inside technology.

What are you interested in when creating your works?

Michelle: We’re interested in creating lo-fi and hands-on understandings of the invisible digital structures that mediate our lives. So far I think our output has mainly been research, attempts to investigate and communicate our findings in playful and active ways in order to create our own languages and motifs for thinking about these things. We’re interested in designing a methodology that requires us to navigate the world differently, reflect and make new sense of our environment over and over again.

Stan: Yeah, I fully agree, It’s a difficult question to answer as it’s almost as if we set out in each project with a suspicion of interest, and carry out a process of incremental research until we find out what that interest might be. We recognise this may be a function of being at a relatively early point in our individual and collaborative practice; when we begin making something we’ve as much to learn about ourselves and the way we make work as the matter of the project itself, and I think this contributes to the heavy integration of our own bodies in our outcomes. Generally though, we share a solid foundation of similar curiosities about the world, often investigating themes of play, post-work and the relationships between humans and invisible digital systems.

How do you gain inspiration for such projects?

M: Conversation has been probably the most generative ideation space for us. The times where we allow ourselves the time or freedom to go down long-winded tangents or veer wildly off-topic is when we know we’ve hit something we’re clearly excited about. So the question becomes how best to set up a space that allows for generative conversation to flow? And this consideration also feeds into the work itself, how can our work create the conditions to catalyse interesting conversation? I think it’s a case of taking the conversation seriously, not just treating it as a serendipitous and fleeting byproduct of the work, but as a valid product itself.

S: I think this is quite a fundamental aspect of what’s drawn us together as collaborators, more so than the common themes that crop up in our individual practices – we both derive so much of our inspiration and creative energy from conversation, passages from articles and books, received wisdom from all areas of expertise; as Miche says, following tangents that burst out, even from just a short word or phrase. At times we indulge in iterative research loops, falling down the rabbit hole, and have recently resolved to incorporate more immediate, intuitive responses into this process, allowing ourselves the confidence to derive more inspiration from within.

Since your collaboration formed during the pandemic and you both are situated across the globe, could you explain the problems and successes you have faced working online together?

M: The main feeling we’ve been trying to bring to our digital studio is the kind of serendipity and play that you might find in shared physical space. My memory of the studio was a lot of hanging around, chatting over a cup of tea, not necessarily the typical picture of ‘productivity’ so we’ve definitely been thinking about how to find that shared idle time online. The slow time of wandering, chatting, getting distracted, procrastinating. While there is definitely a desktop version of procrastination, it somehow doesn’t have the same feeling and joyful effect on the creative process for me.

S: It can be hard not to see this digital reality as a sort of purgatory, we’re constantly making plans for some fictional ‘normal’ time. It’s an ongoing problem that we hit a roadblock labelled “WHEN WE’RE IN THE SAME PHYSICAL SPACE” and have to put an idea on ice. The truth is that there are some ideas that can be disassembled and reassembled to work digitally, and there are some that cannot. As we began our collaboration during the start of the pandemic, however, the work itself never had to undergo that initial offline to online process of transformation that we’ve all been through as people, and so our practice started life calibrated to this Zoom and Google Doc filtered context. This has meant, as Miche said, a lot of examining and aiming to replicate the ephemeral, non-concrete benefits of a studio culture, but our work has adapted to and absorbed the unique conditions we’re all living under.

Your work also focuses on the labour/usefulness of the body/machine hybrid..For example, Bullshit paperwork is a series of lo-fit physical and digital iterations which explore the gamification of labour and bureaucracy as a designed uselessness. Flirting with paperwork as a form of creative output, in response to the endless hoops of “life admin”. What do you think is the purpose of machines? Is it for the ease of life? Or do you think that underneath this ease, lies hidden labour?

M: If you look at the history of any time-saving machinery or device, like the washing machine, it never really saved any time more than merely freeing it up to be filled with another type of work. And I think the same holds true today, take assistive technologies for example that aims to alleviate us of menial everyday labour but in reality just acts to rapt up the expectations we have of our ability to be productive, expanding our capacity for work instead. And I don’t think that’s inherently the fault of the technology, but rather the neoliberal agenda that it embodies. Any critique of technology is almost always a critique of the capitalist employment of technology.

S: This is true, the phrase “purpose of machines” begs the question, “purpose for whom?” The concept of technology just refers to the use of external tools to carry out a task, and it’s a very clever but morally neutral thing that humans have been doing for literally hundreds of thousands of years! Machines have always had the potential to liberate, empower and support us, but the agency isn’t in the nuts and bolts, it’s in the hands of those with the resources and power to shape the development of technology, and those people rarely have the interests of the majority at heart.

There appears to be a lot of experimentation that goes on in your work. Are you looking for answers through these projects? If so, what have been the results?

M: Not necessarily answers but maybe better and more refined questions! I think an answer suggests an endpoint which assumes that our sociopolitical systems are stable and still. But of course, they are living systems that are in constant flux so you can just keep going and going without actually getting much closer, a bit like being on a treadmill! I guess that’s why people spend entire lifetimes dedicated to investigating the same topic, or in a relationship with the same person. It’s always changing so that there is always something new to learn.

What projects are you working on now?

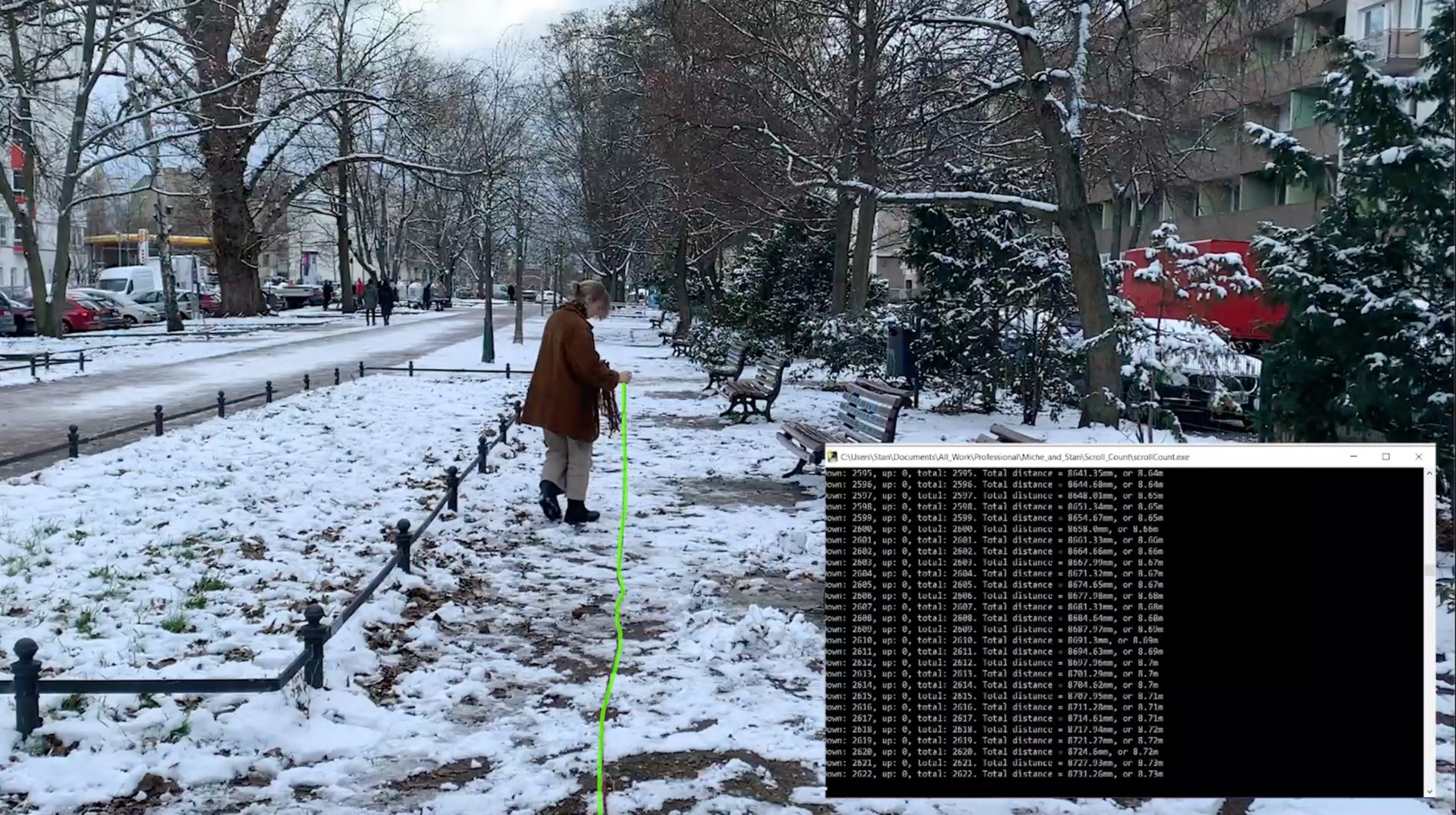

M: We’re coming to the end of a project, still with no name, where we’ve been exploring movement as a tool for digital intimacy. We hosted a series of 1-1 online movement workshops, where we used algorithm-generated instructions to form movements that one of us used to manipulate a clay mould in real-time. We’re just thinking about how to present that project now!

S: We’re just about to start a residency with an organisation called Superfluous in South East London, and will be working on a project called “Bodies of Work.” For that, we’re investigating the creation and consumption of morning routine content on social media, as well as more general concepts of shifting forms of labour and what it means to be productive.