MAGAZINE

The Significance of Self-Exposure and Attention to Content in Nan Goldin’s Photographs

As someone who has difficulty connecting with people and the world while desiring emotional connections, I am constantly mesmerized by artwork exploring interpersonal relationships and desire. Being a photographer is a way to understand myself and the world in order to relate better to the world. Themes of emotions or situations we cannot fully control mainly inspired by personal experiences run through my own research and photographic practice. This is also true of Nan Goldin’s photography work, which has left an impression on me since the beginning of my practice. Photography is also Goldin’s way to deal with relationships and is closely related to her growth. This fits my admiration for the artist exposing herself or her life, as well as her attention to content rather than technical skills involved in the work, and their significance with regard to uncontrollable emotions or situations.

I start the essay with an introduction to Goldin’s key methodology and the sensitive observation shown in her photos. Based on three of Goldin’s works from the past forty years I then analyze Goldin’s practice in relation to the photography field and the development of her work in terms of the techniques and the content, as well as the relationship between her photographs and herself. I conclude the essay with a discussion about the effective skills and mediums in her work.

Goldin’s approach to photography and her ability to notice what others cannot see feature in her work, playing an important part in expressing deep emotions or difficult situations. Her photographs come directly from intimate relationships in her daily life, picturing subjects from youth to death, producing powerful emotions while combined in orders in photobooks or slideshows by showing changes of same subjects including Goldin herself throughout years. She uses film cameras without digital post editing, which not only achieves the purpose of a visual diary, but also generates a deeper connection between herself and her work.[1] Raw and unprotected photos distinguish them from staged or calculated scenes, establishing Goldin in the male-dominated photography field in the late 1970s.[2] Although the content and the style of her practice look like a private documentation, the overlooked details, hidden emotions or psychological states Goldin captures, give her photos powerful sense of art and life. As Krystal Grow describes in Eden and After and early practice:

Goldin is seeking out the secrets children seem to hold, and much like she exposed the raw and unnerving inner lives of drag queens and drug addicts, here she hopes to reveal something about children that is both deeply hidden and transparently evident.[3]

Luc Sante also sees Goldin as ‘a portraitist of souls. She looks through the eyes of her subjects, in both directions, and her purview additionally takes in friends, lovers, artifacts, clothing, rooms: the soul’s context.’[4]Her photography is a mirror that reflects viewers’ experiences. The power of observation and compassion that lead to her photographing those fleeting moments instantly, can hardly separate from the artist’s own life, which in return contributes to the efficiency of her work.

Evidence of the way in which the artist exposes herself that successfully expresses uncontrollable emotions or situations can be clearly seen in The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, 1986. It is a slideshow as well as a photobook about her friends, almost all of whom lived with her and many died from AIDS, honestly showing her friends’ and her intimate life to convey problems in sexual and emotional relationships. The origin of this work goes back to Goldin’s childhood when her sister committed suicide as a teenager. Her family was revisionist, trying to hide the truth from others including Goldin, which is why she thinks revisionism is dangerous. Therefore, Goldin took pictures as proof of life, ‘experiences that no one could revise’ when she was ‘dealing with the difficulty of coupling’ and ‘maintaining intimacy’. This strengthens the power of vivid emotions and the undeniable issues many people have faced, as Goldin and her friends have, about sexual dependency one gets from another person who doesn’t quite fit, and the difficulty in relating.[5] High saturation and flash used indoors form a contrast between urgency of problems and vulnerability of Goldin’s closed small world.

As her defining work, both techniques and content of The Ballad have had a significant impact on the photography field. It was a radical photobook besides Larry Clark’s Tulsa, which had a huge influence on Goldin.[6] It appeared out of place in the art scene when photography was seen as closely related to painting. Its presentation as a slideshow made ‘a revolutionary association’ with ‘the language’ of film. Attention to The Ballad was paid ‘in Europe before’ America, where ‘the postmodern photography of Cindy Sherman and Laurie Simmons’ was prevailing. It has been compared to Diane Arbus’s photographs on a visual aspect. However, their content and purpose are dissimilar, because Goldin’s photographs are ‘anti-ideological’.[7] Eloquent images of addicts inspired heroin-chic photos popularized in fashion magazines such as Detour and ‘advertising campaigns like those for Calvin Klein’.[8] However, Goldin hates that kind of glamorization and she never took pictures of people taking drugs to make them fashionable while it is about honesty and trust.[9] The work is also a model for pictures by a character in film High Art.[10] Her photographs greatly influenced Ryan McGinley.[11] Goldin has developed and achieved the recognition for intimate snapshot style, which makes her a representative in this specific area and also a controversial photographer in a wider photography field.

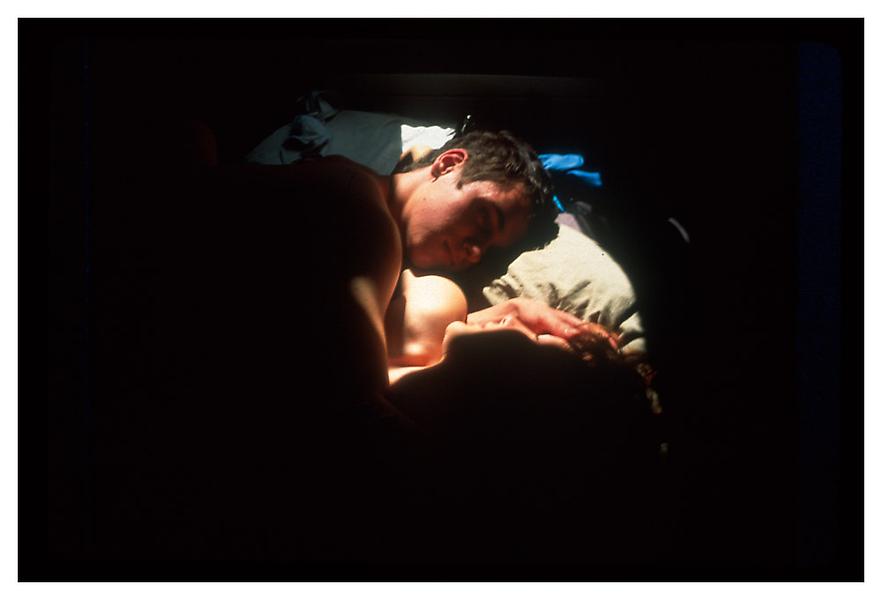

Despite the success of The Ballad has had over the years, the initial public response did not accept Goldin as ‘a good photographer’ in terms of her lack of technique especially in the mainly male dominated world of photography where technical skills were almost necessary for ‘making art’.[12] It is the seemingly casualness and exposure of Goldin herself in The Ballad, which creates a straightforward effect by showing daily reality. This cannot be produced to the same effect by taking care of various technical aspects at the same time. Taking Nan and Brian in bed NYC 1983 (Figure 1) for example, this is a sufficient photo because of the contrasts in this very moment of the post-sex cigarette and the subjects of Goldin herself and her boyfriend.[13] As Angela Anderson highlights, Brian seems ‘unavailable’ while Nan’s gaze shows her dependency and her ‘doubt’ about his response.[14] The intimacy of sex in contrast with the separation after sex generates a sense of loss. The light is so soft while the gap between the couple seems solid and almost tactile, indicating fragility of this relationship. To further show the contrast, Brian may be better positioned in a longer distance to the camera. However, the delicate chemistry conveyed by Goldin’s honesty would likely be broken, which is core of its appealing invitation for viewers to relate themselves. Therefore, technique is not an essential or the only factor to evaluate a photographer but the emotional link and energy generated by content can matter more for photos. Goldin’s emphasis on content is a key element of her being a good photographer, which is shown through years of practice.

In over fifteen years, Goldin has broadened the range of content in her work, for which The Devil’s Playground, 2003 is an outstanding example. It is a photobook divided by themes with texts in between to extract topics it covers. Besides again exposing her friends’ relationships, Goldin turns her vision more to the outside world technically and emotionally. The work extends Goldin’s focus on those usually estranged from society; AIDS patients, heroin addicts including herself, and urban subcultures, as Brooke McCord says, ‘the consequences of their American freedom’.[15] Inclusion of her parents is significant to tell Goldin’s growing openness, based on the history that Goldin ran away from her family at a young age to build her extended family with characters in The Ballad. Her images have become more infused with natural light, rare in The Ballad, although taken no matter what the light is.[16] Goldin’s world is broader and softer, not only constrained in small and dark rooms. However, due to her controversial subject matter, The Devil’s Playground is criticized as vaguely distasteful as a guide to suffering for people not suffering.[17] Whilst it shows difficult problems, it also shows the way people work problems out, unlike The Ballad where Goldin only puts forward problems in relationships without a solution. This was a record of her creating herself through art, carrying Goldin’s concern about new generation’s sex safety.[18]

Since The Ballad, Goldin has developed strength and criticality in her life, influencing her photographs to be more positive and responsible. In the relationship with her photos, Goldin has gained a more active and directive voice where she inputs vitality. Taking Simon and Jessica, faces half lit, Paris, 2001 (Figure 2) in The Devil’s Playground for instance, Simon is Goldin’s nephew, which is surprising with Goldin’s ability of removing discomfort of completely exposed subjects, even though they are a family belonging to different generations.[19] This is a heart-warming and intimate capture, full of sweetness and connection. Only the couple’s faces are lit in the center, strengthening the sense of a whole they build together to exist in a world consisting of encounters they have to deal with. Goldin is not trapped in her small world anymore while she has started to take responsibility as a family member or a mature friend in others’ world, activating the louder voice of her photographs to viewers at different ages. Therefore, I argue that it is not a guide to suffering but an exposure of suffering and struggle people experience and the power and strength they hold or gain to live through difficulties.

About fifteen years later again, Memory Lost, 2019 (Figure 3), is a digital slideshow ‘recounting a life lived through a lens of drug addiction’. This is a more targeted and focused project dedicated to Prescription Addiction Intervention Now, which she founded in 2017 to fight the pharmaceutical companies whose inhumane greed ignited the opioid crisis, the Sacklers particularly.[20] Apart from motivation for recording her friends’ and her lives, Goldin has become more conscious about the selection of a specifically themed series of photos and making use of the effects and power of artwork in society for a certain group of people against a certain organization. It speaks to her ability of building sincere interpersonal relationships and understanding the weakness people usually hide. The fact that this project is based on Goldin’s own experience of fighting against opioid addiction with self-portraits included makes the work more convincing and powerful.

Maturity of Memory Lost can also be seen from a range of subjects and mediums. Goldin has explored further on the use of nature and objects to aid emotional expression. Miserable future addicts cannot see clearly and difficulties with interacting with the world are suggested by the landscapes and skies of low contrast. The power of addiction to make memories disappear is projected onto fire while desire to be free from addiction to maintain or gain belief is expressed by photos of birds, sun and religious icons. The environment where addicts live is revealed by pictures of drugs and the interior. Different contrast of images shows addicts’ unstable moods and existence, and the low quality and high noise indicate the distance and age of memories seeming to them. Content of this slideshow is strengthened by combination of still images, short footage, negative music, recordings of phone messages and interviews, absorbing viewers in narratives. The repeated voice of “wake up” has left me with an impression of the futility of addicts’ screaming at themselves to wake up. Overall it successfully shows the messy, confusing and lost memories due to addiction and conveys addicts’ depressive experiences. However, if paying attention to each single photograph, I doubt the meaning of some photos’ inclusion in the slideshow. For example, it is hard to link photos of some animals on their own to the theme of addiction.

Managing uncontrolled emotions or situations with the work of Nan Goldin has given me more strength to build a strong existence in society by knowing my emotional sensitivity and weakness are shared and understood. Goldin’s work explores themes of relationships that involve intimacy, loss and drug addiction. Her personal experiences and growth are key reasons for the energy in her photos and the shifting themes from overwhelming difficulties, possible resolution to fighting against problematic powers. Compared to her photography technical skills, I think she is more skilled at connecting with people, seeing and reading their emotions and mood, and becoming invisible with her lens while photographing them, which gives her shots natural and lively expression viewers can feel and associate. There are many repetitions of photos in her different work through her active forty years. The arrangement of the sequential presentation creates a stronger narrative with a more logical timeline and obvious relations or contrast through different events of the subjects. Therefore, the value of issues she addresses and roles she plays in her work is more efficiently presented through collections of photographs via slideshow or photobook rather than single photos. Ultimately, Goldin’s success in expressing uncontrollable emotions or situations is significantly contributed to by completely involving herself in the work with her impulse to capture content appealing to her.

[1] Nan Goldin, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (New York: Aperture Foundation, 2012).

[2] James Crump, Variety: Photographs by Nan Goldin (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 2009)

[3] ‘Nan Goldin Illuminates the Short-Lived Magic of Childhood’, Krystal Grow (8 April 2014) https://time.com/3808667/nan-goldin-illuminates-the-short-lived-magic-of-childhood/ [Accessed 20 December 2019].

[4] Nan Goldin, I’LL BE YOUR MIRROR (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1996).

[5] Melissa Harris, Michael Famighetti, Aperture Foundation (eds.), Aperture Conversations: 1985 to the Present (Switzerland: AVA Publishing SA, 2018).

[6] MOCA, Nan Goldin – The Ballad of Sexual Dependency – MOCA U – MOCAtv, online video recording, YouTube, 6 December 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2B6nMlajUqU [Accessed 22 November 2019].

[7] Guido Costa, Nan Goldin (London/NY: Phaidon Press, 2005).

[8] ‘A Death Tarnishes Fashion’s ‘Heroin Look’’, Amy M. Spindler (20 May 1997) https://www.nytimes.com/1997/05/20/style/a-death-tarnishes-fashion-s-heroin-look.html [Accessed 23 November 2019].

[9] ‘Interview with Nan Goldin about new book’, Sean O’Hagan (23 March 2014) https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/mar/23/nan-goldin-photographer-wanted-get-high-early-age [Accessed 30 January 2019].

[10] ‘Cold Dish of Careerism’, Richard von Busack (18-24 June 1998) http://www.metroactive.com/papers/metro/06.18.98/highart-9824.html [Accessed 24 November 2019].

[11] ‘RYAN MCGINLEY’S EXUBERANT DOWNTOWN, 1999-2003’, E. P. Licursi (3 March 2017) https://www.newyorker.com/culture/photo-booth/ryan-mcginleys-exuberant-downtown-1999-2003 [Accessed 24 November 2019].

[12] My view on this has been inspired by my reading of ‘Nan Goldin: unafraid of the dark’, Drusilla Beyfus (26 June 2009) https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/photography/5648658/Nan-Goldin-unafraid-of-the-dark.html [Accessed 26 January 2019]. ‘NAN GOLDIN’S LIFE IN PROGRESS’, Hilton Als (27 June 2016) https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/07/04/nan-goldins-the-ballad-of-sexual-dependency [Accessed 26 January 2019].

[13] ‘Nan Goldin Nan and Brian in Bed, New York City 1983’, Nan Goldin (1983) https://www.moma.org/collection/works/101659[Accessed 19 December 2019].

[14] ‘Intimacy betrayed: Nan Goldin’s ‘Nan and Brian in Bed’’, < https://andersonangelad.wordpress.com/2017/03/22/intimacy-betrayed-nan-goldins-nan-and-brian-in-bed/> [Accessed 20 December 2019].

[15] My view on this has been inspired by my reading of ‘ART; A New Chapter of Nan Goldin’s Diary’, Lynne Tillman (16 November 2003) https://www.nytimes.com/2003/11/16/books/art-a-new-chapter-of-nan-goldin-s-diary.html [Accessed 23 November 2019]. ‘The Devil’s Playground by Nan Goldin’, Charles Darwent (11 January 2004) https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/books/reviews/the-devils-playground-by-nan-goldin-73230.html [Accessed 25 November 2019]. ‘NAN GOLDIN: DEVIL’S PLAYGROUND’, <http://www.stunned.org/goldin.htm> [Accessed 25 November 2019]. ‘Your ultimate guide to Nan Goldin’, Brooke McCord (11 January 2017) https://www.dazeddigital.com/photography/article/34062/1/your-ultimate-guide-to-nan-goldin [Accessed 25 November 2019].

[16] My view on this has been inspired by my reading of ‘Nan Goldin. Devil’s playground’, Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev https://www.castellodirivoli.org/en/mostra/nan-goldin-devils-playground/ [Accessed 25 November 2019]. ‘If I want to take a picture, I take it no matter what’, fotoTAPETA http://fototapeta.art.pl/2003/ngie.php [Accessed 25 November 2019].

[17] My view on this has been inspired by my reading of ‘How Nan Goldin’s Snapshots of Sex, Drugs, and Death Refined Photography’, Loney Abrams (23 July 2016) https://www.artspace.com/magazine/art_101/close_look/how-nan-goldins-snapshots-of-sex-drugs-and-death-redefined-photography-54026 [Accessed 27 January 2019]. ‘The Devil’s Playground by Nan Goldin’, Charles Darwent (11 January 2004) https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/books/reviews/the-devils-playground-by-nan-goldin-73230.html [Accessed 27 January 2019].

[18] My view on this has been inspired by my reading of ‘Nan Goldin: banged up in Reading goal with Oscar Wilde’, Sean O’Hagan (5 September 2016) https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/sep/05/nan-goldin-oscar-wilde-inside-exhibition-reading-prison-artangel [Accessed 25 November 2019]. ‘The dark room’, Sheryl Garratt (6 January 2002) https://www.theguardian.com/theobserver/2002/jan/06/features.magazine27[Accessed 25 November 2019].

[19] ‘Simon and Jessica in bed, faces half-lit, Paris’, Nan Goldin (2001) https://www.matthewmarks.com/new-york/exhibitions/2003-03-01_nan-goldin/works-in-exhibition/#/images/3/ [Accessed 21 December 2019].

[20] My view on this has been inspired by my reading of ‘Nan Goldin brings her empathy and activism to London’, Louisa Buck (21 November 2019) https://www.theartnewspaper.com/blog/nan-goldin-brings-her-empathy-and-activism-to-london [Accessed 23 November 2019]. Nan Goldin Sirens, Marian Goodman Gallery, 2019. ‘Nan Goldin Sirens’, MARIAN GOODMAN GALLERY https://www.mariangoodman.com/exhibitions/351-nan-goldin-sirens/ [Accessed 25 November 2019].

Bibliography

Als, Hilton, ‘NAN GOLDIN’S LIFE IN PROGRESS’ (27 June 2016) https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/07/04/nan-goldins-the-ballad-of-sexual-dependency [Accessed 26 January 2019]

Abrams, Loney, ‘How Nan Goldin’s Snapshots of Sex, Drugs, and Death Refined Photography’ (23 July 2016) https://www.artspace.com/magazine/art_101/close_look/how-nan-goldins-snapshots-of-sex-drugs-and-death-redefined-photography-54026 [Accessed 27 January 2019]

Beyfus, Drusilla, ‘Nan Goldin: unafraid of the dark’ (26 June 2009) https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/photography/5648658/Nan-Goldin-unafraid-of-the-dark.html [Accessed 26 January 2019]

Buck, Louisa, ‘Nan Goldin brings her empathy and activism to London’ (21 November 2019) https://www.theartnewspaper.com/blog/nan-goldin-brings-her-empathy-and-activism-to-london [Accessed 23 November 2019]

Busack, Richard von, ‘Cold Dish of Careerism’ (18-24 June 1998) http://www.metroactive.com/papers/metro/06.18.98/highart-9824.html [Accessed 24 November 2019]

Christov-Bakargiev, Carolyn, ‘Nan Goldin. Devil’s playground’ https://www.castellodirivoli.org/en/mostra/nan-goldin-devils-playground/ [Accessed 25 November 2019]

Costa, Guido, Nan Goldin (London/NY: Phaidon Press, 2005)

Crump, James, Variety: Photographs by Nan Goldin (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 2009)

Darwent, Charles, ‘The Devil’s Playground by Nan Goldin’ (11 January 2004) https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/books/reviews/the-devils-playground-by-nan-goldin-73230.html [Accessed 27 January 2019]

fotoTAPETA, ‘If I want to take a picture, I take it no matter what’ http://fototapeta.art.pl/2003/ngie.php[Accessed 25 November 2019]

Grow, Krystal, ‘Nan Goldin Illuminates the Short-Lived Magic of Childhood’ (8 April 2014) https://time.com/3808667/nan-goldin-illuminates-the-short-lived-magic-of-childhood/ [Accessed 20 December 2019]

Goldin, Nan, I’LL BE YOUR MIRROR (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1996)

Goldin, Nan, ‘Nan Goldin Nan and Brian in Bed, New York City 1983’ (1983) https://www.moma.org/collection/works/101659 [Accessed 19 December 2019]

Goldin, Nan, ‘Simon and Jessica in bed, faces half-lit, Paris’ https://www.matthewmarks.com/new-york/exhibitions/2003-03-01_nan-goldin/works-in-exhibition/#/images/3/ [Accessed 21 December 2019]

Goldin, Nan, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (New York: Aperture Foundation, 2012)

Garratt, Sheryl, ‘The dark room’ (6 January 2002) https://www.theguardian.com/theobserver/2002/jan/06/features.magazine27 [Accessed 25 November 2019]

Harris, Melissa, and Michael Famighetti, Aperture Foundation (eds.), Aperture Conversations: 1985 to the Present (Switzerland: AVA Publishing SA, 2018)

‘Intimacy betrayed: Nan Goldin’s ‘Nan and Brian in Bed’’, < https://andersonangelad.wordpress.com/2017/03/22/intimacy-betrayed-nan-goldins-nan-and-brian-in-bed/> [Accessed 20 December 2019]

Licursi, E. P., ‘RYAN MCGINLEY’S EXUBERANT DOWNTOWN, 1999-2003’ (3 March 2017) https://www.newyorker.com/culture/photo-booth/ryan-mcginleys-exuberant-downtown-1999-2003 [Accessed 24 November 2019]

McCord, Brooke, ‘Your ultimate guide to Nan Goldin’ (11 January 2017) https://www.dazeddigital.com/photography/article/34062/1/your-ultimate-guide-to-nan-goldin [Accessed 25 November 2019]

MOCA, Nan Goldin – The Ballad of Sexual Dependency – MOCA U – MOCAtv, online video recording, YouTube, 6 December 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2B6nMlajUqU [accessed 22 November 2019]

Marian Goodman Gallery, Nan Goldin Sirens, 2019

MARIAN GOODMAN GALLERY, ‘Nan Goldin Sirens’ https://www.mariangoodman.com/exhibitions/351-nan-goldin-sirens/ [Accessed 25 November 2019]

‘NAN GOLDIN: DEVIL’S PLAYGROUND’, <http://www.stunned.org/goldin.htm> [Accessed 25 November 2019]

O’Hagan, Sean, ‘Interview with Nan Goldin about new book’ (23 March 2014) https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/mar/23/nan-goldin-photographer-wanted-get-high-early-age[Accessed 30 January 2019]

O’Hagan, Sean, ‘Nan Goldin: banged up in Reading goal with Oscar Wilde’ (5 September 2016) https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/sep/05/nan-goldin-oscar-wilde-inside-exhibition-reading-prison-artangel [Accessed 25 November 2019]

Spindler, Amy M., ‘A Death Tarnishes Fashion’s ‘Heroin Look’’ (20 May 1997) https://www.nytimes.com/1997/05/20/style/a-death-tarnishes-fashion-s-heroin-look.html [Accessed 23 November 2019]

Tillman, Lynne, ‘ART; A New Chapter of Nan Goldin’s Diary’ (16 November 2003) https://www.nytimes.com/2003/11/16/books/art-a-new-chapter-of-nan-goldin-s-diary.html [Accessed 23 November 2019]