MAGAZINE

The Wonderful World of Ayla Hibri

Ayla Hibri (b. 1987) is a visual artist from Beirut, Lebanon currently based between Amman and Beirut. For the last decade, Hibri has been in constant travel, shifting environments to maintain a continuum of displacement and discovery. She has collected an expansive archive of visual data on the psychogeography of places and the ubiquitous aspects of the human condition. In parallel, she paints and draws creatures and worlds far removed from this one, driven by the matter of dreams and imagination.

How would you describe your art?

My art, whether it’s photography, drawing or painting is a tangible pause, an arrested moment that I endeavour to transcribe. It is raw, organic and imperfect. My work plays with polarities, some of it whispers, some of it screams, some of it is blunt some of it is subtle. It honours the beautiful and the grotesque, the mundane and the divine, the hilarious and the tragic. My primary language is colour.

Why do you create art?

I use art as a tool to understand and reflect on existence, human nature, nature, myself, the visible and the invisible. I try to zoom out and contemplate the bigger picture and ask more philosophical questions: Where did we come from, why are we here, what is a country, a culture, what are the origins of a thought? Photography is the filter through which I interact with the outside world and painting is my vessel to the inner world. Both mediums complete each other, give me balance and a poetic way to cope and perceive.

What is the creative scene like in Beirut?

Beirut has been plagued by political corruption for many decades, and finally came to its breaking point, leading to the October Protest in 2019. Everything has changed, and we’re starting to look back on our “scene” with nostalgia. Between the pandemic, the financial collapse, the August 4th explosion and a dreadful political class, Lebanese people are genuinely traumatized. Lebanon is in its darkest hour. So I can’t really tell you what the scene is like at the moment but I can tell you that brilliant creative minds are always emerging from there, from all generations. Some are there trying to fight, preserve and persevere, some are looking for a way out, while the rest have migrated. I can assure you though, the Lebanese scene will re-emerge with vengeance, and soon.

Despite living in Beirut and Amman, you are constantly travelling. How does your location have an impact on your work?

Everything impacts my work: the city’s energy, the season, the weather, the light, my mood, my anxiety levels, the music I’m listening to. It’s all connected and everything I do is a reflection of that. I love working in different environments and actively pursue it.

Beirut inspires me like no other place. Amman is the place for me to work with fewer distractions. It is quiet and slow and I have the desert just a couple of hours away.

You are a DJ, researcher, storyteller, painter and photographer. I fell in love with your paintings but it appears that your photography is most well-known. What came first?

Photography first came to me as an adult. The painter in me was dormant for the last 10 years, but it was my favourite thing to do as a child. My undergrad is in interior architecture, which was great while it lasted and it led to me discovering photography. Not so long after I graduated, I went to pursue my studies in photography in Chicago. I fell in love not just with the act of taking photos, but the history and theory of photography as well. After that, I travelled all around and lived in different places with the aim to take photos. Walking, exploring, road-tripping, looking, observing, I never left home without a camera. With time, I built an expansive archive of ‘moments’. One day around 6 years ago I read a small essay by Italo Calvino that resonated with me. In one passage it said:

“The minute you start saying something, ‘Ah, how beautiful! We must photograph it!’ you are already close to the view of the person who thinks that everything that is not photographed is lost, as if it had never existed, and that therefore, in order really to live, you must photograph as much as you can, and to photograph as much as you can you must either live in the most photographable way possible or else consider photographable every moment of your life. The first course leads to stupidity; the second to madness.” [1]

Not too long after reading that, I was devastated when I found all the photos I shot of the carnival in Brazil came out blank; I was unaware that my camera was broken. In frustration (and a touch of overdramatization), I borrowed some paint and a canvas from my studio mate and filled a canvas with fireworks of the memory of a colour, a smell, a feeling of euphoria. It was like revenge and I felt more liberated than I felt in a long time. I returned home to Lebanon with a renewed sense of purpose. I needed to slow down in both my life and photography, to process my experiences, take a step back and be more selective with what to photograph. I went inwards, learned about the psyche, the mind, the spirit, synchronicity. I tuned into my imagination and the invisible. I kept drawing and painting and a new channel of self-expression opened up. In parallel, I started working on my photography book which was published in 2019. It was all shot in Lebanon and it took 4 years to come together. I established my rhythm: slow photography and a daily practice of painting and drawing.

What do you look for when taking a photograph?

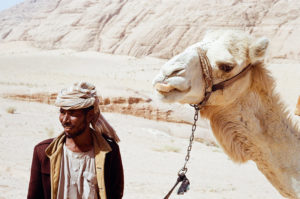

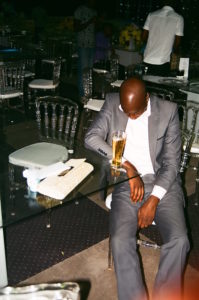

On the one hand, I look for what stands out for me, on the other hand, I take photos that expand my collections. One of the things I did when I changed my tempo was to go through every photo I’ve ever taken from all the different countries I visited over the years looking for common denominators. I noticed I had unconscious patterns and themes that kept reappearing. So I divided them up into categories (animals, food, people sleeping, empty playgrounds) and now I have my own personal system. A kind of parallel world that reaffirms the universal, a no man’s land that transcends borders, geography and time.

Your paintings have a strong focus on the ‘figure’ – can you tell me more about this?

“The figure” is my intervention on reality. It is the application of imagination on elements and features that are taken from the real and stretched in all kinds of directions, taking it to another dimension. One that is different and otherworldly but recognizable.

Where do you get the imagery from?

I invent them but I access them through visualizations, dreams, memories, free associations, myths and stories I’ve come across.

“The Smoker” is one of my favourite artworks of yours. A painting that at first glance, shows an everyday solitary figure slouched over a rock. But on closer inspection, the figure has a devil’s tail, red nail varnish, four nipples, a bow tie and a blue physique. The temporal space has been shifted. What is the incentive in converging the real and imaginary in your art?

It is where I, the painter, and you, the viewer, converge. These details you mentioned carry symbols and metaphors with meanings that waver between the mundane and the cosmic by virtue of the beholder’s imagination. It’s human nature to look for hidden messages and interpret coincidences, symbols or signs as an attempt to create order from the chaos of being. This process acknowledges and unveils the intertwining of the conscious and unconscious in us that we tend to ignore or suppress. By me conceiving it and you trying to piece it together in your own way, it is an exercise in opening the channel between the human spirit and the wisdom of the divine.

Bibliography

Calvino, Italo. “The Adventure of a Photographer” in Difficult Loves. United States: Mariner Books, 1970.

Images

Ayla Hibri. Accessed April 21, 2021. https://www.aylahibri.com/nomansland

Ayla Hibri. The Burn. 2017. 120 x 80 cm. Acrylic on canvas. Accessed April 21, 2021. https://www.aylahibri.com/paintings

Ayla Hibri. The Smoker. 2017. 130 x 110 cm. Oil on canvas. Accessed April 21, 2021. https://www.aylahibri.com/paintings

Ayla Hibri. Underworld. 2019. 225 x 184 cm. Oil on canvas. Accessed April 21, 2021. https://www.aylahibri.com/paintings

Ayla Hibri. Accessed April 21, 2021. https://www.aylahibri.com/studio