MAGAZINE

Thoughts about spaces on screens

Screening Situations in virtual exhibitions

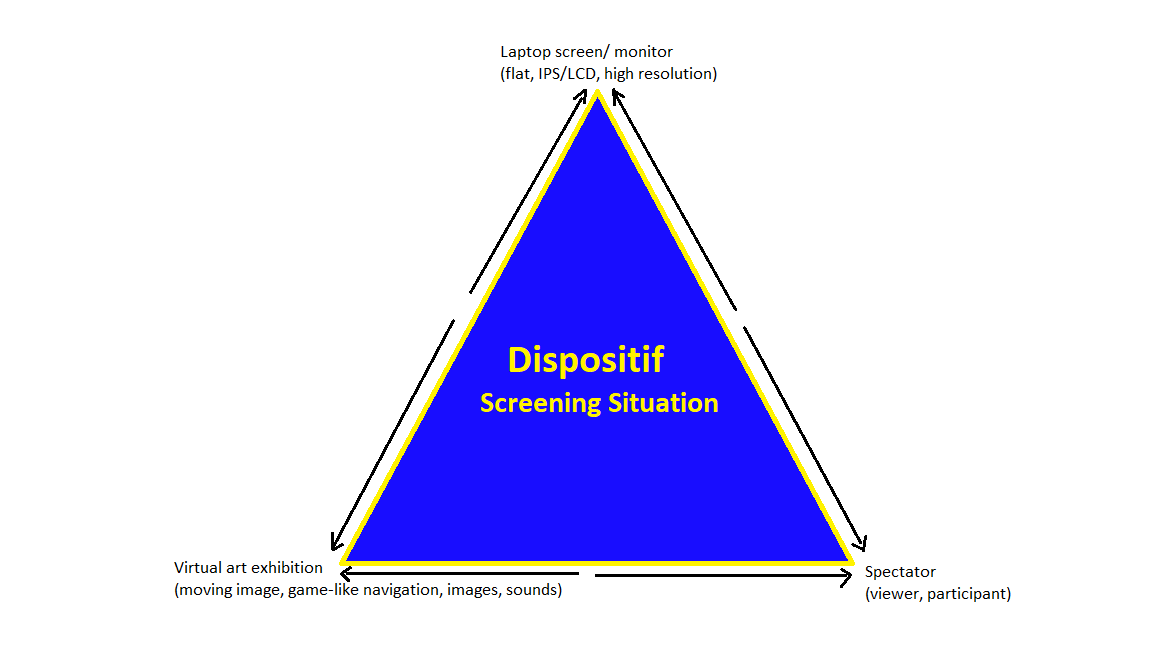

The concept of “dispositif” refers to screening situations and comes from film studies (Kessler 2006). The concept implies it is not only about the screen or its content, referred to as “text,” but also about the space and its materiality in which it is positioned. The “dispositif” is derived from film studies that later became a central analytical tool for screen studies in a broader context than cinema. It is useful to look at how conventional modes of address, framing and institutional practices changed around screen technologies as well as how the spectator is positioned in relation to the screen. Furthermore, with the emergence of new media, screening situations showed new ways to position spectators in front of screens or become “attached” to screens (VR, 360 cinemas, mobile screens, etc.). Therefore, as an analytical tool, “dispositif” can be used to identify new situations related to the triad of “text” – screen – spectator and how these three elements challenge conventions or reinforce them.

For example, a virtual exhibition viewing from a laptop or desktop proposes a somewhat conventional mode of address and mode of looking from positioning the spectator in front of a screen. However, the “text”, in this case an exhibition, is somewhat unconventional to be engaged with virtually. Therefore, the experience and how the spectator relates to it changes, creating a new mode to experience art.

Art usually is closely tied to institutions like museums or galleries, spaces that are “clean”, promising a specific way to experience artworks. These clean spaces are sterile, separated from the outside world. A long line of conventions and shifts foreground this conception and connotation of exhibition space throughout art history. With current restrictions and the lack of mobility due to the pandemic, many art institutions and artists are rethinking how they exhibit artworks. As a response, many art practitioners have moved into the digital space where current technologies allow various modes of exhibiting. From blog spaces, websites, and social media platforms, artists now collaborate with programmers or create spaces where the “white cube” galleries can be recreated. These virtual exhibition spaces invite the spectator to explore the artworks in a space designed specifically for the exhibited artworks. Some of these virtual spaces even play on the senses and immerse the spectator in their offered experiences.

For example, Hivemind by wendy.network in the Cryptowoxels virtual space allowed the spectator to walk through the space using the keyboard and look around with the touchpad or mouse. The exhibition also offered an auditive experience with the sound of footsteps while walking in the space created. Although based on the on-site, offline, embodied visit to a gallery, this multisensory and playful situation creates a highly different art-viewing experience. The lack of materiality of works and the generated environmental sounds make the spectator aware of their own presence differently. A different experience of embodiment can be observed through the touch of the mouse/touchpad that helps with navigation, and the sound that reminds us of walking can create immersion. Thus, the relation between artwork and spectator is significantly different in the virtual space than in a gallery.

Art exhibitions usually present artworks that are not only 2-dimensional images but also material objects with different textures organized in a space strategically for the spectator. This situatedness of the spectator in relation to artwork is crucial in art. Historically artists conceived their artwork with the spectator in mind (of course, there are exceptions). Now, transporting the idea of an exhibition in virtual space somehow changes this situation. The spectator’s position becomes fixed, watching a screen where the perception of the exhibited objects happens through the eye, stripping away the other senses. Therefore, the content changed from artworks present in their material reality to images of artworks displayed in a space where our physical bodies cannot relate to them except through the immersive and playful affordances of the virtual realm.

Liveness in Hivemind

Since the pandemic, there is an abundance of live events, streams, happenings, lectures and all kinds of meetings that we had been accustomed to in physical forms. However, liveness is not something new on our screens. The television introduced very successfully liveness where we could watch something on our screens knowing that others are doing the same thing simultaneously. Liveness on the Internet is different from liveness in broadcast television since it is not only referring to the shared temporal aspect of this one-to-many medium but rather the individual experience of “navigation through cyberspace, our sense of actively constructing our own flows and pathways through the (often static) objects available there” (Tara McPhearson in Auslander 119)

So, this sense of navigation through cyberspace then introduces the spatial aspect of liveness on the internet at the expense of losing the shared social and temporal aspect of live broadcasts. Yet, suppose I think about the virtual exhibition Hivemind by wendy.network on Cryptovoxels. In that case, I still think of a shared spatial and temporal aspect, more so, direct two-way communication between spectators turned users in this virtual navigable world.

Hivemind in Cryptovoxels emphasizes the liveness through its navigable space that transports the users into the gallery spaces and streets constructed in this fabricated world. The users gain a virtual body. However, they are identical. In contrast to McPherson’s notion of internet liveness as an individual experience, Hivemind could be individually visited while sitting in front of the computer and shared through the chatbox where users could interact with each other.

In the case of visiting an exhibition, presence is always a necessity for the artworks, the setting and the spectator as well. So, I would say, Hivemind succeeded in constructing a space that does not necessarily remodel reality but creates an alternative, where visiting an exhibition is not just about displaying the artworks but also about its social aspect. Drawing on the idea of interfaces as dispositifs argued by Karin van Es in her lecture about Liveness and Liveness as dispositif (2021), I think this is achieved through the dispositif of this particular exhibition. Although Hivemind cannot be visited anymore, the exhibition constructed a space where the spectators were always getting a ‘live feed’ of who else is in the gallery interacting with the exhibits.

References

Auslander, Philip. 2016. “The Liveness of Watching Online: Performance Room.” in Perform, Experience, Re-Live, edited by Cecilia Wee. London: Tate Public Programs, 112-129.

van Es, Karin. 2021. “Liveness,” part 3. Online lecture, Utrecht University, Utrecht, May 20.

Kessler, Frank. 2006. “The Cinema of Attractions as Dispositif.” In The Cinema of Attractions Reloaded, edited by Wanda Strauven. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 57-69.