MAGAZINE

Wangechi Mutu deconstructs our ways of seeing by exploring gendered and racialized identities as mapped onto the female body.

Something interesting is happening to the questions we are asking about ourselves. Coronavirus has reminded us that we are mortal. Whatever advances and cures that science will make, we are only too aware that we are embodied. It has challenged us to notice that the way things have been can no longer dictate how things will be. Time to question how and who we are with one another. Time to question how we have been with one another. Time to imagine new ways of seeing.

We have come a long way in our understanding of the myriad ways that women have been objectified and we have begun the journey of seeing how long and pervasive the shadow of colonialism is. But it’s one thing to see it and it’s another to escape the cultural drive to conform. Media culture draws us in and not to conform is to acknowledge the power of the dominant form – to still follow that Instagram page which promotes the new best lip product or read that magazine which tells us how to dress and care for our skin is to still conform to the ideal image of a woman.

Frantz Fanon, the French West Indian philosopher famously said that to speak a language is to take on a world, a culture. [1] Fanon claims that language forms us and by immersing ourselves within a language, we are immersing ourselves within a particular culture. Thinking about the Black Lives Matter movement makes us aware of how deeply entwined all our culture is interlaced with a shameful colonial past. How do we go forward knowing this?

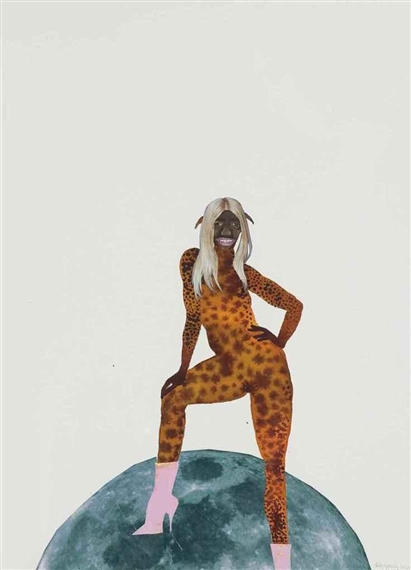

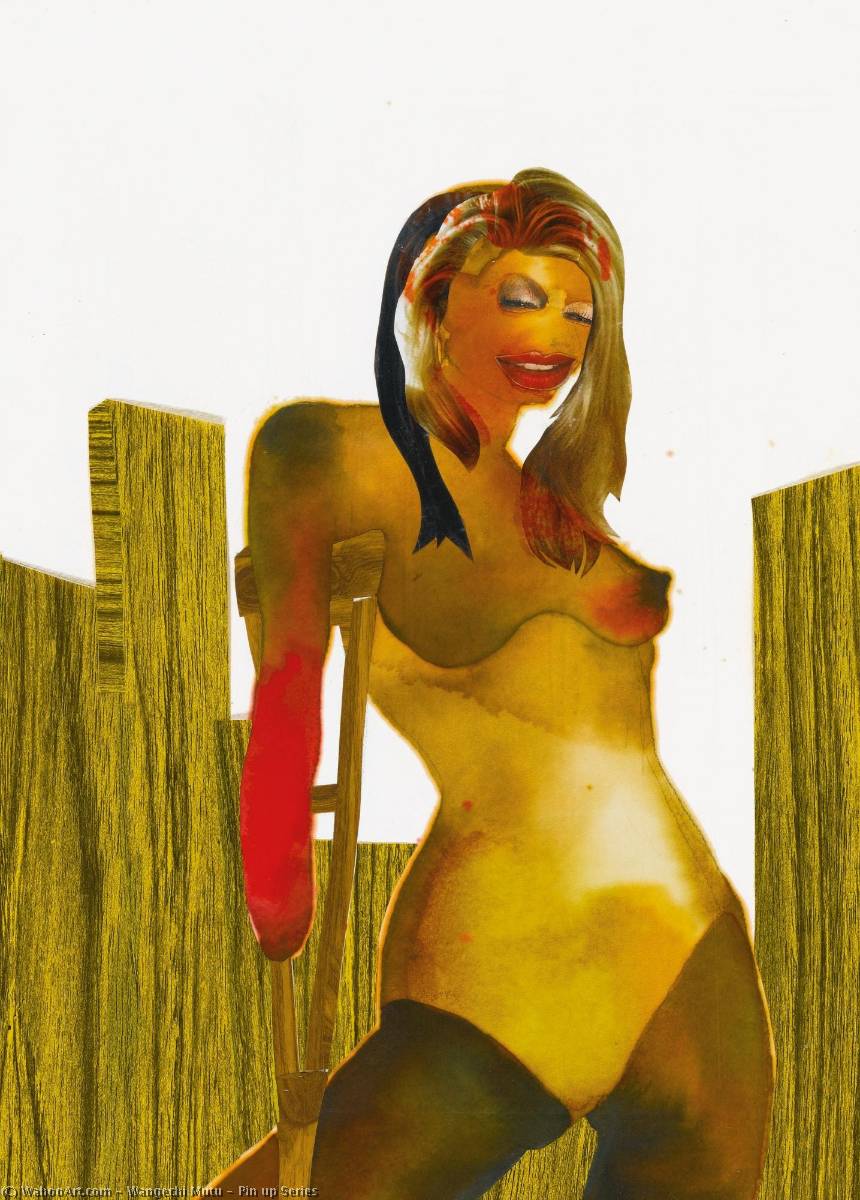

Wangechi Mutu is an artist who seeks to examine the complexity of identity. Mutu, the Kenyan-born artist who lives in Brooklyn, New York, creates artworks extending from sculptures to variously sized collages on paper and Mylar. The use of collage and assemblage are important artistic strategies for the artist, who uses them to explore gendered and racialised identities mapped out onto the female body. Take, for instance, the ‘Pin-up’ works which display the female form in sexualised poses. Like two iconic powerful black female figures, Grace Jones and Josephine Baker, Mutu displays her female figures as hyper-sexualised black female stereotypes. She does this as a confrontational commentary highlighting the absurdity of commonly conceived stereotypes.

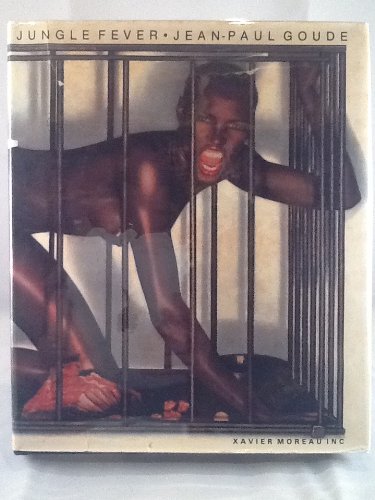

Like Jean-Paul Goudes famous Jungle Fever photograph which displays Grace Jones on all fours in a cage, Mutu displays female figures reminiscent of sexy calendar girls – legs separated, clothes taken off. They are extremely erotic and exoticised. By displaying such potent signifiers of race and gender, she makes racist and sexist cliches artificial and unreliable. Enhancing the stereotype of “feminine” “animal” they become de-essentialised. Instead of the “black feminine” always being marginalised, Jones and Mutu maximise their existence and breathe this sort of life by emphasising such features. As well as such emphatic features being an ironic commentary they are highlighting the ridiculousness of these stereotypes.

Furthermore, on closer inspection, their immaculate sexual poses are highlighted as being false. Limbless bodies and bloody cuts created through violence become visible. Mutu lures the viewer in with the display of provocative cliche poses before being repelled with the sight of violence and mistreatment. Here Mutu confronts the viewer, destroying the airbrushed perfect image in favour of a more realistic image of the female. As such Mutu redefines our image of beauty maimed limbs and all. She displays the intentional repulsive image of women in order to step away from perfection and allow others to become more acceptant of their own.

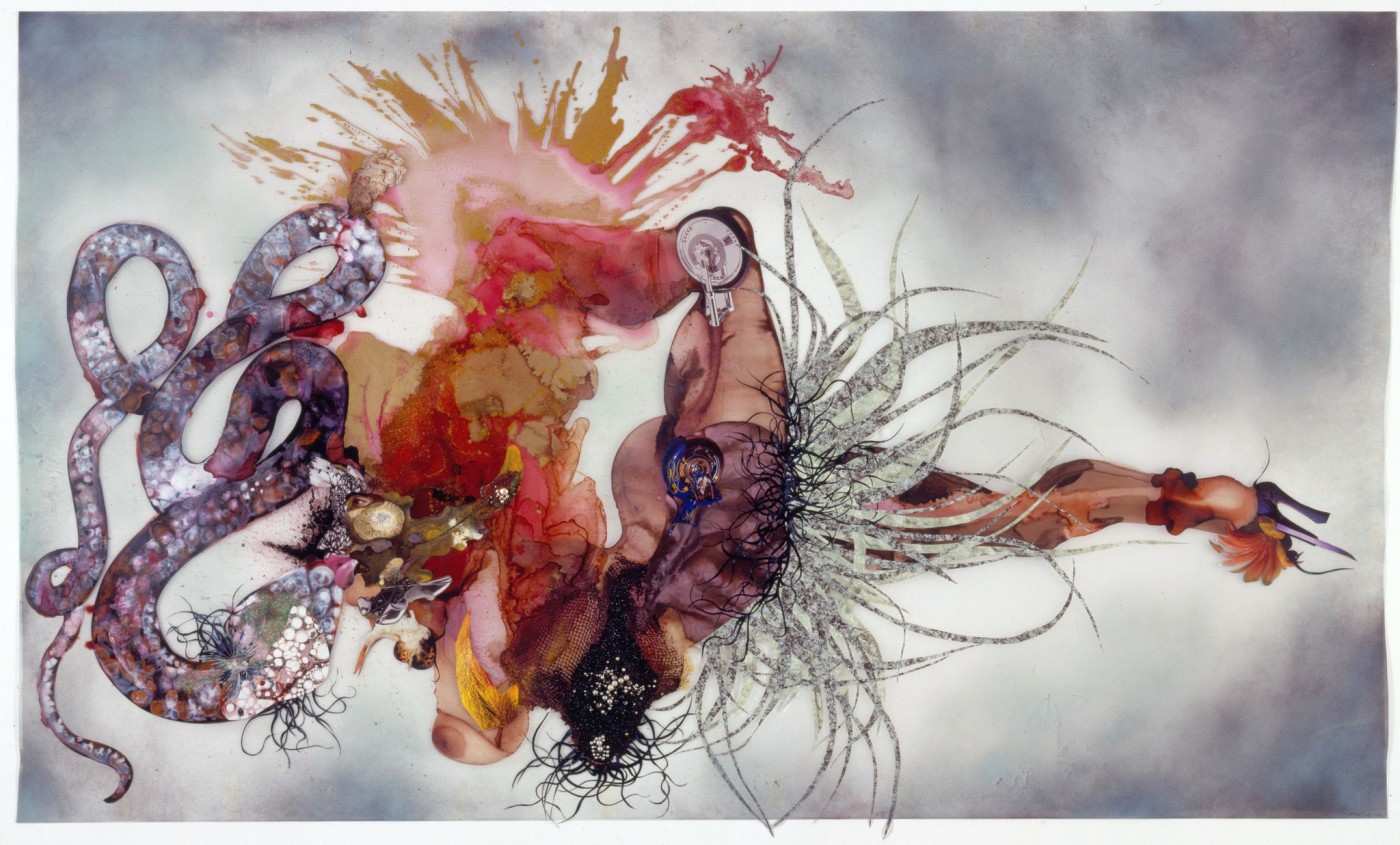

Tricking the viewer once again, Mutus figures also revel in boundary confusion. Using the idea of the cyborg, a hybrid of human-animal-machine, Mutu reimagines what the human is, thus dismantling old fashioned ideas of the body. Using cut out images sourced and found in popular culture, ethnographic and fashion magazines, Mutu creates crossbred collaged characters with amalgamations of various living organisms. Take for instance “Non, je ne regrette rien” A maimed figure – part human, part animal, part machine- suspended in a grey and brown abyss. The top leg is equipped with a bike wheel that connects to spinal tubing. The centre of the image occupies a black root-like structure emerging from the creature’s torso. Parts spill over the edge of the canvas and various formations are visible. The arrangement of human, animal, plant and mechanical parts suggests a type of mutilation that results in a dismembered body, where the figure’s identity is unrecognisable and thus unable to be categorised.

Wangechi Mutu examines how the female body has been categorised, regulated and disciplined by demonstrating figures that are constantly involved in a process of becoming, changing and transforming. Hierarchies of man over woman, West over East, human over animal, are destroyed. The confusion of boundaries creates a break in the social system. Wangechi Mutu states that her work is “a type of surgery. It is a destructive process. A way of destroying a certain set of hierarchies.” [2]

COVID has deconstructed our ways of being, Mutu deconstructs our ways of seeing – we need to question who we have been and how we are with one another… the future is about to be reimagined.

Bibliography

Fanon, Franz. “The Negro and Language” in Black Skin, White Mask. New York: Grove Press, 2008.

Louisiana Channel. “Wangechi Mutu: Cultural Cutouts.” Youtube. Last modified March 5, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KWd64sQK_yU.